For a long time now I have had a fascination with South Africa. I cannot say if it is through knowing South Africans, through taking two college courses that focused on South Africa, or just a natural interest aroused by the idiosyncratic nature of the country. The parallels between South Africa and America are well documented – as Robert Kennedy said in 1968, both can be described as

a land settled by

the Dutch in the mid-seventeenth century, then taken over by the British, and

at last independent; a land in which the native inhabitants were at first

subdued, but relations with whom remain a problem to this day; a land which

defined itself on a hostile frontier; a land which has tamed rich natural

resources through the energetic application of modern technology; a land which

once imported slaves, and now must struggle to wipe out the last traces of that

former bondage.

While I was in South Africa over the 2016-2017

Christmas and New Years holidays, I saw that South Africa had a lot of the same

problems as America – but theirs are ratcheted up to an exponential level. The

racial tensions, income inequality, runaway university tuition expenses, and

government corruption are certainly familiar to me, but in South Africa the

stakes are much higher. I believe it is these commonalities that made me want

to learn more about the country.

So

I did what anybody does when they want to learn more about a foreign country –

I immersed myself in it second hand. I read about the history and politics, I

read the literature (Coetzee, Brink, Abrahams, Gordimer) and, of course, I

watched relevant films. This being a film blog, it is the films in particular I

want to write about here.

I

want to start off by making a distinction between films about South Africa and

films made by South Africans. There are many quality films made about South

Africa by the outside world, usually delving into the nation's history – films such as Zulu,

a 1960s British film that shows a British military force successfully fend

off a superior Zulu force, while not belittling the Zulus with problematic

stereotypes – rather, the Zulus are shown to be smart in their tactics and

military manoeuvres. Another great film about South Africa is Breaker Morant, a film about the Boer

War that focuses on a military tribunal but also includes some excellent dramatizations

of the war; although Australia has to pass for South Africa, it works as a

moving drama. The Boer War (1899-1902) was fought between two competing white

peoples in South Africa - the British fought against a settled group of

Dutchmen (called Boers, or Afrikaners) who had already been in that country for

more than two centuries. Unfortunately, when the war was over, the black

population, which made up the majority of South Africa, fell victim to the

white reconciliation, leading to almost a century of Apartheid, the legal

separation of the black natives and the white settlers. Breaker Morant is an excellent look at this conflict, and helps to explain

the divisions that would shape South Africa.

What helps me to

understand South Africa more than those films, however, is films produced by

South Africans. In 1916, in the first decade after the Boer War and the

establishment of a South African state, a production company called Africa

Films released the first South African film, De Voortrekkers. This is

a short epic (less than an hour long) that chronicles the beginning of the

Great Trek and the Battle of Blood River. In the 1830s, in response to British

administration of formerly Dutch territory, the Afrikaners began to migrate

eastward in search of new lands, in what is known to history as The Great Trek.

The first people to move northeastward were called Voortrekkers, where this movie gets its name. Several of these Voortrekkers, including their leader Piet Retief,

were brutally murdered by Dingane, King of the Zulus; this was met with

retaliatory violence, culminating in Zulu submission after the Battle of Blood

River.

These facts form

the quasi-mythological founding of Afrikaner South Africa. The details of the

Great Trek have been known to generations of Afrikaner schoolchildren; it is an

incomplete version of history, as it only focuses on the Afrikaner trials,

rather than on the natives that they met along the way, who were not pleased to

find their land and lives suddenly expendable. De Voortrekkers, made over one hundred years ago now, sparked the

birth of South African cinema – and like Birth

of a Nation in America, christened the birth in white supremacy.

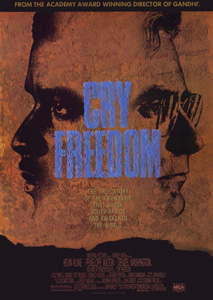

Few films were

made in South Africa during Apartheid, and few of that limited number are worth

mentioning. There is the comedy The Gods

Must Be Crazy (1980), which is

good for a few laughs, and Cry Freedom (1987), a shocking indictment of the Apartheid

system that surprisingly, in a moment of South African glasnost, was allowed to

be screened domestically. Cry Freedom is

a biopic about two people – Steve Biko, the father of the black consciousness movement,

and Donald Woods, the journalist who made Biko famous outside of South Africa, and

who was himself subsequently forced to flee the country following Biko’s death at the hands of the police. I read Biko’s book, I Write What I Like, as a college student; it was meant to be a

powerful weapon for the victims of oppression, and still holds up decades later. I have a strong

memory of reading his instructions on how to be a better white ally – by stop

trying to “help” black people and instead by telling other white people,

especially those in a position of power, to stop attacking blacks physically,

socially, and economically. It is a powerful book, and was, of course, banned

in South Africa until 1994. The fact that the censors allowed this film through

meant that the Apartheid system was coming to an end.

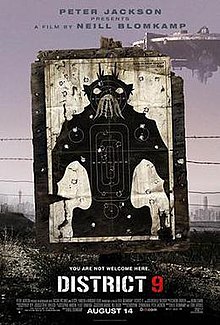

Since the end of Apartheid in 1994, there have been a series of popular South African films that were co-produced by the United Kingdom or the United States, many of which have been quite popular in terms of box office receipts and critical reviews. Sarafina!, Cry the Beloved Country, District 9, Invictus, and Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom are some examples of co-productions that were set in South Africa. For the most part, these films seek to contrast the horrors of Apartheid with the new South Africa, a country where minority rule has ended and new struggles have emerged. Several of them are quite hopeful for the future of the country – without hiding the difficulty of reconciliation.

Apartheid was a miserable time that is hard for outsiders to fully comprehend. The totalitarian government that ruled from 1948-1994 had, while in opposition, supported the Nazis during the Second World War. Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd, Prime Minister from 1958 until his assassination in 1966, openly discussed the possibility of exterminating the black population, which vastly outnumbered the whites; he only held back on this genocide because he feared how many white people might die in this process. The ruling Nationalist Party developed nuclear weapons, with the thought of possibly turning them against the black population, who were concentrated into sections of the country called homelands, or Bantustans. These weapons were dismantled shortly before political power was handed over to the native population in the early nineties. The black majority did not simply suffer silently – acts of freedom fighting (or terrorism, as the Afrikaners saw it) were common; this is why Nelson Mandela was imprisoned on Robben Island for over two decades. The film Sarafina! depicts the 1976 riots in the Soweto township, which culminated in the burning of schools by the local residents – they wanted an authentic education, not the subpar bantu education that forced them to learn the oppressors language (Afrikaans) and was designed to keep them from achieving independent thought.

Apartheid was a miserable time that is hard for outsiders to fully comprehend. The totalitarian government that ruled from 1948-1994 had, while in opposition, supported the Nazis during the Second World War. Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd, Prime Minister from 1958 until his assassination in 1966, openly discussed the possibility of exterminating the black population, which vastly outnumbered the whites; he only held back on this genocide because he feared how many white people might die in this process. The ruling Nationalist Party developed nuclear weapons, with the thought of possibly turning them against the black population, who were concentrated into sections of the country called homelands, or Bantustans. These weapons were dismantled shortly before political power was handed over to the native population in the early nineties. The black majority did not simply suffer silently – acts of freedom fighting (or terrorism, as the Afrikaners saw it) were common; this is why Nelson Mandela was imprisoned on Robben Island for over two decades. The film Sarafina! depicts the 1976 riots in the Soweto township, which culminated in the burning of schools by the local residents – they wanted an authentic education, not the subpar bantu education that forced them to learn the oppressors language (Afrikaans) and was designed to keep them from achieving independent thought.

Apartheid has now

been over for twenty-four years. Modern day South Africa can feel like a bit of a mixed bag. In its favour, it remains the second strongest economy on the

continent, while enjoying the most pro-human rights constitution on the planet

(South Africa became the first country to legalise gay marriage in 1994). There

are vineyards and villas that are the envy of anywhere in Europe or North

America, with breathtakingly beautiful sights. South Africa also continues to

host an impressive medicinal ability – in 1967, South Africa was the location

of the world’s first heart transplant; in 2014, South Africa was the location

of the world’s first penis transplant. At the end of last year, Jacob Zuma, the

openly corrupt president, was ousted in favour of Cyril Rhamposa, one of the authors of

the 1994 constitution.

While this is all

to be commended, there is also much to be worried about. South Africa has the

highest Gini coefficient in the world, meaning that they suffer the world's worst

income inequality – an ultra rich at the top and abject poverty at the bottom,

with little in between. This leads to extreme violence, even compared to other

African countries – it is estimated that a violent crime occurs once every

thirty seconds, and Cape Town is consistently listed as one of the most

dangerous cities in the world. The ANC government, once a beacon of hope, is corrupt, and increasingly the

black youth seem to be interested in the far left Economic Freedom Fighters

(EFF), led by a man named Julius Malema, who has openly called for the death of

Boers and the creation of an ethno-communist state. While calling for death is

clearly wrong, it is easy to see where the resentment comes from - two decades

after Apartheid, the whites still own over seventy percent of the land, while

the black majority still resides mostly in townships and rural farmlands.

It is the stories

of these continually oppressed blacks that make for the final two films I want

to talk about here, Yesterday (2004)

and Tsotsi (2005). One of South Africa’s more infamous claims to fame is that it has

the highest rate of HIV/AIDS in the world. As many as one in five South Africans

have HIV/AIDS, a number that was growing rapidly in previous decades but has since

levelled off as awareness has grown. Yesterday

tells the story of a woman named Yesterday who lives in a rural village and

must travel for hours on foot to see a doctor. Her husband works deep

underground in a mine in Johannesburg, far away from her, and she does not get

to see him very often. She is very sick, but she does not know what exactly is

wrong with her, and she tries to hide her sickness from everyone - especially

her young daughter, Beauty. One day, her doctor informs her that she has AIDS.

She is shocked – we are not told exactly what happened, but the assumption is that her husband had already been infected with it when they met. When she

tries to tell him this, he savagely beats her.

It is the stories

of these continually oppressed blacks that make for the final two films I want

to talk about here, Yesterday (2004)

and Tsotsi (2005). One of South Africa’s more infamous claims to fame is that it has

the highest rate of HIV/AIDS in the world. As many as one in five South Africans

have HIV/AIDS, a number that was growing rapidly in previous decades but has since

levelled off as awareness has grown. Yesterday

tells the story of a woman named Yesterday who lives in a rural village and

must travel for hours on foot to see a doctor. Her husband works deep

underground in a mine in Johannesburg, far away from her, and she does not get

to see him very often. She is very sick, but she does not know what exactly is

wrong with her, and she tries to hide her sickness from everyone - especially

her young daughter, Beauty. One day, her doctor informs her that she has AIDS.

She is shocked – we are not told exactly what happened, but the assumption is that her husband had already been infected with it when they met. When she

tries to tell him this, he savagely beats her.

Yesterday does not ask us to pity its

characters; it asks for recognition, not condescension. Yesterday is a strong

woman who is determined to build a private hospital for her husband and to live

long enough to see her daughter go to school. She is not an educated woman – in

one particularly striking scene her doctor asks for a signature, and she meekly

admits to not being able to read or write – but she knows the power of

education, and wants to make sure that her daughter can lead a better life than

hers has been. Despite being a film where the main character is dying of AIDS, Yesterday is a hopeful story, one that

asks us to disagree with her father, who named her Yesterday because “things

were better yesterday”, and have faith in a better tomorrow.

Tsotsi has a similar message. Like Yesterday, Tsotsi follows an eponymous

title character as he navigates a life of poverty and violence in post apartheid South

Africa. It has been said that although there are eleven official languages in

South Africa, everyone shares a mother tongue – violence. That is true for

Tsotsi, a young, stone-faced killer from the townships. The film pivots around

a scene where Tsotsi steals a car from a wealthy black woman, and in the course

of the theft, shoots her in the stomach. He soon realises that her three-month-old

baby is in the back seat, and that is when his life is irreversibly altered.

Tsotsi has a similar message. Like Yesterday, Tsotsi follows an eponymous

title character as he navigates a life of poverty and violence in post apartheid South

Africa. It has been said that although there are eleven official languages in

South Africa, everyone shares a mother tongue – violence. That is true for

Tsotsi, a young, stone-faced killer from the townships. The film pivots around

a scene where Tsotsi steals a car from a wealthy black woman, and in the course

of the theft, shoots her in the stomach. He soon realises that her three-month-old

baby is in the back seat, and that is when his life is irreversibly altered.

How many movies

and TV shows tell the same old narrative, of a mild-mannered individual who

gets caught up in events beyond their control and turns evil? Tsotsi dares to flip the script on the

banality of evil, and instead portrays a man who is living a life of

irredeemable wickedness, but through the consequences of his actions he learns how to be a better person. Tsotsi begins

to have a moral crisis after inadvertently kidnapping the baby, so much so that

he finds that he cannot kill a man that he and his fellow gangsters have tied

up in a subsequent robbery. He realises that all of his life he has been

nothing but a wicked criminal, and that he wants to be better – and then he

starts to take corrective action. Tsotsi inspires

hope that, for all of its problems, for all of its dark history, South Africa

has a brighter future ahead of it. Over ten years later, South Africa is still

waiting.

This is a really interesting piece, Malcolm, thanks so much! I’d be fascinated if you could shine the spotlight on other countries as a means of illustrating their film history... other African countries first, perhaps?

ReplyDelete