“The attack yesterday morning was no stain on the honor of France, and certainly no disgrace to the fighting men of this nation. But this court martial is such a stain, and such a disgrace. The case made against these men is a mockery of all human justice. Gentlemen of the court, to find these men guilty would be a crime, to haunt each of you till the day you die. I can't believe that the noblest impulse of man-- his compassion for another-- can be completely dead here. Therefore I humbly beg you...show mercy to these men.”

- Colonel Dax, Paths of Glory

Stanley Kubrick was the greatest auteur to ever stand behind a camera. He is certainly considered by many critics and other filmmakers to be the definitive director, mastering each genre with a single film before moving on to the next. Kubrick was notorious for his perfectionist approach to filmmaking, spending years on a single film, and was equally notorious for his supposed curt and unapproachable private life. To add to the mystery of Kubrick, he rarely gave interviews, and was an extremely unprolific director; in Kubrick’s almost fifty years of filmmaking, he only made 13 feature length films, and over half of them were made the first fifteen years of directing. Following a dispute over the filming of Spartacus, Kubrick put himself in charge of everything – he not only directed, but typically wrote, produced, edited, chose the music for, and did the cinematography for all of his own films, as well as ran the advertising when the films were released. It is extremely rare for a director to have as much control over their own films as Kubrick. In the end, the point of Kubrick’s larger than life pictures was never to explain or answer anything, but always to raise more questions. Almost all of his films have great debates surrounding their meanings, and Kubrick himself declined to offer any deep insight, claiming that it would ruin the films if he tried to explain them.

Stanley Kubrick was born into a non practicing Jewish family in Manhattan on July 26th 1928. Although his parents and teachers described him as bright, Kubrick held a D average while at school, and claimed that an education did not really interest him. On his twelfth birthday, his father, a doctor, gave him a chess board, something the young Stanley would cherish for the rest of his life. On his thirteenth birthday, his father gave him an even greater present – a camera. Kubrick instantly fell in love with photography, developing his skill whenever possibly over the next few years. In early April, 1945, Kubrick sold his first photo, one of a newspaper vendor looking depressed next to a newspaper stack announcing the death of U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, to Look magazine for twenty dollars. This photo captured the mood of the nation, who was upset to lose the president who had gotten them out of the great depression and who was about to win the Second World War for them. Look magazine eventually hired Kubrick as a photographer for them, where he remained until he began making films.

While working for Look magazine, Kubrick began filming short documentaries for RKO Pictures. His first documentary, Day of the Fight, is a fifteen minute film that follows the daily life of a boxer before he gets into the ring, who quickly wins his boxing match. His second short, Flying Padre, is about a New Mexico reverend that flies to various churches to deliver his sermons. Kubrick described both of these films as silly in a 1969 interview.

After creating two financially successful shorts, Kubrick decided to undertake the ambitious project of a full length film. He quit his job at Look magazine to focus full time on this film, one that he made using independent financing. In 1953, Fear and Desire, the story of a group of soldiers during an unnamed war who get trapped behind enemy lines, was given a limited release. Kubrick personally disliked the film and bought all of the available prints after the film left theater’s to ensure that it was never widely seen again. His personal dislike for the film is likely due to the difficulty he had making the film – his first wife, his high school sweetheart Toba Metz, left him while the movie was being made. To this day it still has not had a wide commercial release.

Kubrick’s second film, Killers Kiss, was also independently financed by him, family, and friends. This early film foreshadowed his later film The Shining, using a showdown scene involving an attempted axe murder. Killers Kiss tells the story of a failed boxer who gets involved with a woman who is in with the mafia, and the consequences of his involvement. Kubrick’s subsequent films would have similar three way struggles. His second wife, Ruth Sobatka, played the ballerina in a cameo role.

The first screenplay that Kubrick based on a book would be his next film, The Killing. Based on Lionel White’s novel Clean Break, The Killing is a fifties film noir that follows a non linear plot structure, telling the story of a horse race heist gone wrong. Produced by James Harris, The Killing was the first of three films the two would make together under the name Harris-Kubrick Productions. Although The Killing was neither a great critical or commercial success, time has been extremely favorable to this early Kubrick classic, and it is today on the Internet Movie Data Base top 250, along with seven of Kubrick’s other twelve films. The film also gathered the attention of other directors, actors, and film critics. Quentin Tarentino’s first film, Reservoir Dog, was modeled in plot structure after this film; Tarentino cites Kubrick as a major influence.

Although The Killing is now well respected, Kubrick’s first truly groundbreaking film was unarguably Paths of Glory. This Harris-Kubrick production was an anti war adaptation with dialogue that could have been written by a modern day Shakespeare. There is one scene in particular, where one soldier asks another if they would rather die by bayonet or machine gun fire. When the other soldier answers with machine gun fire, the first soldier reasons then that he is not truly afraid of death, but more so afraid of pain. As the story goes, Kubrick presented the screenplay to Hollywood star Kirk Douglas, who told him that this film would never make any money, but it had to be made because of its poignant subject matter. Douglas’ prophecy proved to be correct, as the film failed to turn a profit and was banned from most European countries, including Germany, where the movie had been filmed. Despite the fact that the hero is unable to prevent the court martial of three innocent soldiers, the film ends on a high note, as Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas) is able to expose the malevolence of the French command and is offered a promotion for his role. The film ends as a German girl sings a beautiful melody to a group of rowdy hostile French soldiers at a bar, who slowly calm down to this music and begin to hum along with her. Kubrick fell in love with the actress playing the German girl, Christiane Harlan, and divorced his second wife to marry her. They were married for the rest of his life.

In 1960, Kirk Douglas selected Kubrick to replace Anthony Mann as the director of Spartacus, having enjoyed his collaboration on Paths of Glory. Spartacus was Kubrick’s most ambitious film to date. In Spartacus, Kubrick had his only ever subservient role, where Kirk Douglas was the executive producer and controlled many of the aspects that Kubrick wanted to control. This created a great tension between the two, who had become close during Paths of Glory. This is also the only film where Kubrick was not involved in writing or casting. In the end, Kubrick felt that he must be in complete control of every aspect of his films from then on. Spartacus became a great financial and critical success, and helped to solidify the still young Kubrick’s name as a great director. Peter Ustinov earned an Academy Award for best supporting actor as the slave dealer and gladiator trainer Lentulus Batiatus, the only actor to earn an Oscar under Kubrick’s direction.

Harris-Kubrick Productions made their last film together in 1962, when Vladimir Nabokov’s extremely controversial novel Lolita was released on the silver screen. For the early nineteen sixties, Lolita, the story of a married man who has a sexual affair with his fourteen year old step daughter, was really pushing the boundaries. Kubrick wanted to make the film as faithful as possible, but the standards of his time did not give him much to work with. In the end, most of the sexual conduct was left up to innuendo and the viewer’s imagination, and Kubrick famously said "had I known what I would've had to cut out, I probably wouldn't have made the film." Filming for Lolita took place in England, and the Kubrick family moved there while working on the film, never to return home afterwards.

Kubrick’s next film, Dr. Strangelove, was supposed to be a serious film to capture the cold war fears of nuclear annihilation. While writing the screenplay, one based on Peter George’s thrilling novel Red Alert, Kubrick found himself having great difficulty writing a straight story about this subject, deeming most of the issues too funny to deal with directly. Ultimately, after an unsuccessful attempt at writing a serious film, Kubrick decided to make the film a black comedy, and hired a satirist to help with the screenplay. Dr. Strangelove or: How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb satirizes the cold war setting, daring its audience to laugh at the idea of nuclear warfare that would bring about the destruction of the whole human race. Kubrick would become infamous for such juxtapositions, later setting beautiful classical music over violence and rape scenes in A Clockwork Orange. In Dr. Strangelove, Peter Sellers plays three very distinct characters, as Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, a career serviceman who was tortured by the Japanese in a POW camp in World War II, President of the United States Merkin Muffley, a somewhat timid midwesterner who is in charge of the war room meetings, and as Dr. Strangelove, a presumable German nuclear physicist who once worked for the Nazis, now works for the United States creating weapons. Each character has very distinct mannerisms and personalities. George C. Scott and Slim Pickens fill out the other leading roles, Scott as General Buck Turgidson, an over the top all American hero type, and Pickens as Major T.J. “King” Kong, a rowdy cowboy pilot who risks everything for America, including riding on top of the nuclear bomb as it is dropped on a Russian base. Dr. Strangelove, like other films such as The Manchurian Candidate and Seven Days in May capture the cold war paranoia zeitgeist; what sets it apart from these films, which are extremely dark and hard to watch more than once because of their subject matter, is that it brings audiences back for multiple viewings due to its engaging hilarious style.

In 1965, Kubrick met with science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke with the idea of making the definitive science fiction film. Clarke recommended several of his published books, and Kubrick separated individual pieces for the film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Together, they decided to write a screen play and a novel, both to be written at the same time, with both collaborators contributing to each other’s work. 2001, which was released in 1968, was not instantly a classic, most people who went to see it came out scratching their heads, unable to determine what the film was about. The films tenure in the theatre was almost over when Warner Brothers found that it would be a lot more profitable to leave the film in, due to the fact that younger fans were returning to the theatre, attempting after multiple viewings to discern the films meaning. Over time 2001 has become Kubrick’s most studied film, with no definitive unarguable message truly discernable even ten years after the date the film refers to. 2001 gave Stanley Kubrick his only Oscar, for best visual effects.

Due to the fact that 2001 was released the year before the moon landing and had a very similar moon aesthetic to that of the real moon many conspiracy theorists who claim the landing was a fraud claim that Kubrick directed the “staged” moon landing.

After 2001, Kubrick’s next project was to be an epic film portraying the events of Napoleon and the Napoleonic Wars. Kubrick did extensive research for this film, supposedly having read every single book that his assistants brought to his attention. Kubrick had entered negotiations with a couple European nations to use their armies for Napoleon when the similar styled film Waterloo was released. Although it was well received by critics, it was a monetary failure and this caused the financial backers to pull out of production. Heartbroken, Kubrick was forced to move on, scraping this project all together.

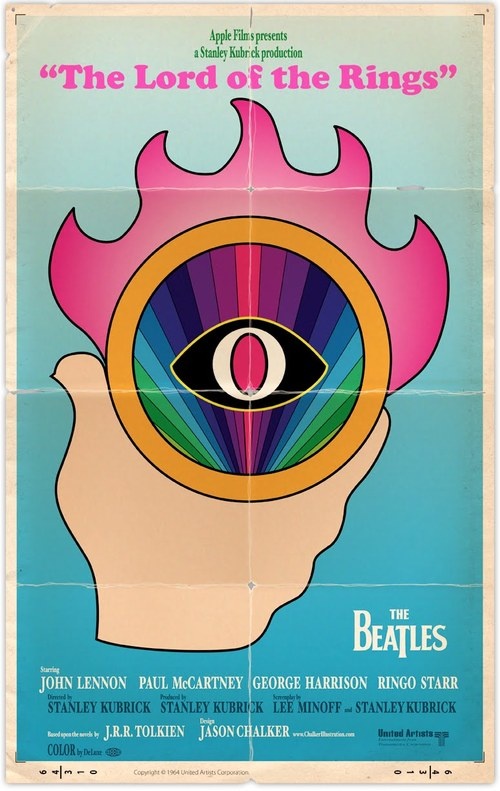

In the late 1960’s, Kubrick was approached by The Beatles. They wanted to hire him to direct J.R.R Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, with Paul McCartney as Frodo, Ringo as Sam, George Harrison as Gandalf and John Lennon as Gollum, and Kubrick briefly considered making the film. J.R.R Tolkien publicly was against the film, and the film never got made.

After the failure to create a Napoleonic epic, Kubrick put together the 1970 adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. The novel presented several difficulties; for starters, it was written in an entirely made up language, a combination of Russian and cockney slang, and it was also graphic, violent, and extremely sexual. Malcolm McDowell, who plays the leading role Alex DeLarge, was able to fake the artificial language due to experience in Shakespearean Theatre, and Kubrick toned it down a little bit so that audiences would be able to understand the dialogue. Although he compromised on the language, Kubrick refused to compromise on the sex and violence, and A Clockwork Orange ultimately received a rare X rating from the MPAA in America. The film was released in less than two years after pre production had begun, and became, by a wide margin, the quickest Kubrick film on record. The violence in the film was widely imitated in Britain, and these imitators prompted death threats to be sent to Kubrick’s home, demanding that he pull the film from theatres. Kubrick, in a rare display of directorial power, appealed to Warner Brothers to pull the film from English theatres. Although it was detrimental to further profits, Warner Brothers complied. There are very few directors who have that power over their film companies, and they only gain that power due to the fact that these companies want to keep the directors happy so they will continue to make films for them.

After five years, Kubrick’s next film, Barry Lyndon, was released to theatres. An adaption of William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon, Barry Lyndon is a eighteenth century period piece that tells the story of an adventurous young Irishman, who travels around Europe getting himself into all sorts of trouble. Kubrick took great care to make this film look eighteenth century, going to wild extremes such as only using natural light for virtually the entire film. This meant, for all the interior and night time scenes, candles were used as the primary light source. The technique pays off enormously, as it provides a very distinct visual for the entire film. Further lengths entailed using eighteenth century props and costumes, as well as asking that leading roles stay indoors months prior to filming, so that their skin would be extremely pail when production began. Barry Lyndon was not the commercial success Kubrick and Warner Brothers had been hoping for; despite the lead actor Ryan O’Neal’s star power in Hollywood, the film did not recoup its costs in America, although it did perform fairly better in Europe.

In an effort to make a film that would both be commercially viable and satisfy Kubrick’s artistic ability, Kubrick’s next project would be an adaptation of Stephen King’s early best seller The Shining. Stephen King initially wrote a screenplay for Kubrick, who turned it down immediately in favor of one he wrote himself, and often ignored King’s attempted contributions to the film, such as casting and writing advice. Principal photography for The Shining took over a year to complete, and filming took even longer. With The Shining, Kubrick set a world record for most film used on a single film, filming over two hundred hours and spending weeks on single scenes. His harsh treatment of Shelly Duvall, who played Wendy Torrance in the movie, has become somewhat legendary, as he would often single her out and accuse her of wasting the time of everyone on set. This was a way of Kubrick getting her to play the most defeated and desperate woman on the film that she could possibly play. The copious amounts of retakes of particular scenes are accredited to Kubrick getting the actors to feel like they were trapped inside the film, as their characters were trapped inside the hotel. The Shining, like most Kubrick films, received mixed reviews when it came out. Kubrick was nominated for a Golden Rasberry (“Razzie”) for worst director in the awards first year of existence, and now The Shining is considered to be one of the best films of its genre ever released. Despite its reputation as a chilling horror flick, Kubrick personally felt that The Shining was his most optimistic film, because of the use of ghosts, which promised a life after this one.

Kubrick had been increasing the time in between each film, spending five years on Barry Lyndon and The Shining, and it would be seven more years until his next film Full Metal Jacket hit theaters. As opposed to Paths of Glory, which had been pointedly anti-war film, this film took no moral standpoint on war; Kubrick’s intention was merely to show war as it happened. Full Metal Jacket was well received upon its release, but it does not get the same in depth studies as his other films. It is a two part film, like most of Kubrick’s films, with the first half taking place in a military boot camp, and the second half taking place in Vietnam. Like all of Kubrick’s later films, it was filmed in England, where we had to go through great measures to make the countryside and abandoned parts of cities resemble battlefields. Full Metal Jacket was ultimately overshadowed by Oliver Stone’s Vietnam War film, Platoon, which ended up winning best picture the same year it was released.

Kubrick’s next project was to be a holocaust film titled The Aryan Papers. The film was canceled before filming began when Kubrick heard about Steven Spielberg’s similar styled Shindler’s List. After being overshadowed by Platoon and enduring heartbreak when his Napoleon project had to be canceled because of the failure of Waterloo, Kubrick thought it best to avoid making films similar to those in the cinemas. Kubrick later explained that, having read extensively on the Holocaust, it was impossible to display this horrible historical incident on to film and have it come close to its true awful nature.

Kubrick’s last film, Eyes Wide Shut, was an adaptation of a nineteen twenties novella titled Traumnovelle (“Dream Story”). Eyes Wide Shut is still, to this day, questioned by critics as whether or not it is as great as his other films, although pretty much every one of his films was given questionable ratings upon their initial release. Kubrick himself said that Eyes Wide Shut was the best film he ever made. Released in 1999, Eyes Wide Shut was release a full twelve years after Full Metal Jacket. The principle actors, Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, who were then a married couple, signed open ended contracts, as Kubrick was aware that he would want to film them over long periods of time. The actual filming took the better part of two years, with Harvey Keitel and Jennifer Jason Leigh having to withdraw from filming due to other obligations. As he had done with Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick took a dark subject matter and juxtaposed to a lighter motif, here mixing an all powerful dangerous secret society with the Christmas season. On March 7th 1999, four days after screening a completed Eyes Wide Shut for Warner Brothers, Stanley Kubrick died in his sleep at the age of seventy. It is debated whether or not he had truly finished working on the film. Kubrick was afterwards buried on the grounds of his manor, under his favorite tree.

Artificial Intelligence, or AI, is a Stephen Spielberg film released in 2001, gives Kubrick a posthumous producing credit. Kubrick came up with the idea in the 1970’s, but held off until production until the nineties, when he asked Spielberg to direct and offered to personally produce it. Although the film was released after Kubrick had died, his ideas and innovations made their way into the finished film. The film not only includes a production credit for him, but it is also dedicated to his memory. Also released in 2001 was the definitive documentary about the film maker, Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures. Using interviews from his collaborators and fellow directors as well as archival footage and movie clips, the film traces the life of Kubrick through his films. The film was commissioned by his family, to quench the rumors that painted Stanley as an angry recluse.

Although Kubrick is considered to be one of the most original filmmakers of all time, all of his films, with the exception of Fear and Desire, Killers Kiss, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, were based on books. Kubrick was extremely well read, and while he would base a film off of one single book, he would read several books of similar nature to supplement his knowledge on a single subject. A great example of this is his unmade Napoleon film, where he supposedly read over one hundred books he had his assistants buy him on the subject of Napoleon Bonaparte and the Napoleonic Wars. The exceptions to this rule consist of his first two films, Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, which had a book released about the same time as the film by the screenplay’s co-writer Arthur C. Clarke. In varying levels his films diverged from the books, his most faithful adaptation being A Clockwork Orange, despite leaving out the final chapter, and least faithful being Dr. Strangelove, which Kubrick made up the titular character for.

Stanley Kubrick was not easily intimidated by MPAA and censorship violations, and was uncompromising in his vision for his films. At certain times during his career, this made things difficult for him. Paths of Glory was banned in France, Switzerland, Germany, and Spain during its release for how it portrayed the French military. Lolita, the story of a fourteen year old girl who has sex with an older man married to her mother, was extremely censored by the studios, and Kubrick once famously said that if he had known just how restricted he would be he probably never would have made the film. A rare X rating was given to the theatrical version of A Clockwork Orange for its depictions of violence and rape. Stanley Kubrick personally decided to pull the film from theaters in England after crimes inspired by the film were committed, even though doing so would slim the profits. Warner Brothers, who wanted to keep Kubrick happy in every way possible, complied. A Clockwork Orange remains one of two X rated films to be nominated for the Best Picture Oscar, the other being Midnight Cowboy. For his final film Eyes Wide Shut, to avoid an X rating in America bodies were superimposed in the editing process to cover up the sexual intercourse during the famous orgy scene. Kubrick died before the film was put into theatres, and it has been speculated as to whether or not he would have allowed this censorship had he lived longer.

One of Kubrick’s greatest criticisms was that he focused too heavily on the darker side of humanity. This criticism can be applied directly to the endings of his film, which are always dark and can leave the audience somewhat depressed. In a typical Kubrickian denouement the protagonists are either left dead or significantly worse off than other realistic outcomes could have allowed. Even in his earliest of films, this statement rings true. The Killing is comparable to a Shakespearean tragedy, due to the fact that all of the principle characters are dead by the end of the film. In Paths of Glory, Colonel Dax fails to prevent the unjust court martial of three French soldiers, and these three are shot dead by a firing squad. Kubrick’s next film, Spartacus, has our hero crucified in the end of the film, having lost all hope of combating slavery and Roman decadence. In Dr. Strangelove, perhaps Kubrick’s darkest film, the world’s population is vaporized with the Russian doomsday device. Although the original novel provided a happy ending, our humble narrator Alex is “cured” of his peaceful ways at the end of A Clockwork Orange. Kubrick, who only heard of the books happy ending when the screenplay was almost finished, decided to leave it out, citing it as unrealistic. Barry Lyndon, which has a more lighthearted tone than most of his other films, also includes a dark ending, as our protagonist has his leg shot off by his own stepson, and is destined to return to the rags after spending the entire film racing after riches. Due to its horror genre, The Shining’s grim ending is more fitting than his other films were, where Jack Torrance goes after the lives of his family after losing his sanity trapped in the malevolent Overlook Hotel all winter. Although not strictly speaking the end of the film, the end of Full Metal Jacket’s first act displays humanity at its darkest, as the newly graduated marine Private Leonard Lawrence’s mind snaps and he decides to take the life of the hardened Sergeant Hartman, before killing himself. Kubrick’s swan song Eyes Wide Shut does not necessarily end on a low note, but dark themes are explored throughout the film, such as sacrifice, infidelity, and secret societies.

Several critics have noticed that Kubrick uses a very similar facial shot in a number of his films. Roger Ebert, in particular, dubbed this particular shot as the Kubrick glare. The glare, first used in A Clockwork Orange, is a high angle close up shot that looks down onto a face glaring blankly forward, representing a characters descent into madness. Jack Torrance has the same facial close up in The Shining, while he is alone in the hotel and his family is lost in the ground’s hedge maze. Gomer Pyle is shown with Kubrick’s famous glare twice in Full Metal Jacket. First, when Sargeant Hartman asks the marines about the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the Ruby Ridge siege; second, when Pyle is in the island bathroom with a fully loaded rifle. Some critics say that the HAL 9000 is depicted with this same glare, but it is hard to verify that as the computer does not have any facial features besides a single eye. Lastly, a famous picture of Kubrick himself in his final years features him with the infamous glare. This picture can be seen at the top of this blog.

Bathrooms are where human beings release their most primal and animalistic tendencies. There is nothing glorious about anybody using a bathroom, be it nobility or a lowly peasant. This concept seems to have intrigued Kubrick, as many pivotal moments in Kubrick films take place in bathrooms. For example, in Dr. Strangelove, Brigadire General Jack Ripper, who has launched the attack that will bring about the end of the world, takes his own life by a bullet hole to the head in a bathroom. In 2001: A Space Odyssey the bathroom door shows a set of extremely complicated instructions on how to operate a toilet in space. This shows how different man’s most primal function is in outer space. When Alex is found badly beaten by a man who he crippled and killed the wife of, he is put in a bathtub to recover. In the bath he absent mindedly starts singing “Singing in the Rain,” and this gives away who he truly is. Redmond Barry reconciles with his wife while she is in a bathtub in Barry Lyndon. This is a rare redeeming shot of a bathroom for Kubrick, who normally reserved the bathroom for darker uses. The Shining uses the bathroom moreso than any other Kubrick film. First, Jack encounters a naked woman in a bathroom, even though the hotel is supposed to be empty. She approaches him and they embrace, but when he looks at her again she is now old and her skin is melting off. Jack shrugs the thing off as an isolation induced hallucination and decides not to tell anyone about it. The next big bathroom scene in the film takes place when Jack meets the ghost of Delbert Grady, the hotel’s previous caretaker, in a bathroom. Grady informs Jack that he never actually was the caretaker of the hotel, and that it has always been Jack. “You’ve always been the caretaker here. I would know, I’ve always been here.” The final, and most iconic bathroom scene of The Shining takes place as Wendy locks herself in the bathroom and Jack attacks the door repeatedly with an axe. Jack Nicholson improvised the famous “Here’s Johnny” line, a reference to The Johnny Carson Show, which he says as he is forcing his way into the bathroom. The climax of the first half of Full Metal Jacket, the murder suicide of Sergeant Hartman by Private Gomer Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio), takes place in the boot camp bathroom late into the night. Private Pyle commits suicide while sitting down on the toilet. At the beginning of Kubrick’s final film Eyes Wide Shut Dr. Bill Harford (Tom Cruise) is called in to help a prostitute who has gone catatonic in a bathroom after taking a speedball.

Although Kubrick very purposefully avoided making multiple films of the same genre, he often came back to the greatest of all human follies, war. His first film, Fear and Desire, takes place behind enemy lines during an unnamed war. Although not much information is readily available about this film, this is the fact that has been made quite apparent through the available clips and interviews. Four years later Kubrick would make a proper war film with Paths Of Glory. This film, a decidedly anti-war piece, tells the story of an impossible attack over No Man’s Land by the French army during World War I that led to a court martial of three troops who were involved. In 1964, Kubrick used the nuclear panicked Cold War as a backdrop for his film Dr. Strangelove. The film famously ends with a depiction of nuclear war, set about to bring destruction to the earth. One of the very few films to depict the Seven Years War is Barry Lyndon, wherein Barry fights for both the English and the Prussian armies. Although this is not the focus of the film, it is still a key element in developing Barry Lyndon’s character. Like Platoon, Good Morning Vietnam, and Apocalypse Now, Kubrick was among a handful of directors who decided to make Vietnam films in the 1980’s, his being Full Metal Jacket. This was neither pro nor anti war, just an attempt to make a film about war in general. These conclude Kubrick’s finished films about war, but it is worth mentioning that both his unmade Napoleon film and Holocaust film would have both been surrounded by wars, each of extremely large proportions. Kubrick, who viewed the world in ways that have been described as misanthropic and ironically pessimistic, would have been obviously obsessed with war, especially in ways that emphasized its dehumanizing qualities. War gave Kubrick a chance to show humanity at its absolute worst, and show how people interacted at rock bottom.

Kubrick’s personal appreciation for classical music became very apparent throughout his films, starting with 2001: A Space Odyssey, where Kubrick scraped the entire original score for the film in favor of Richard Strauss’ Thus Spake Zarathustra and Johann Strauss’ The Blue Danube. Kubrick connected the gracefulness of satellites revolving round the Earth to the smoothness of this classical music. For his next film, A Clockwork Orange, the classical music a reference to Alex’s favorite musician, Ludwig Van Beethoven. The graceful, beautiful score for this film is a direct juxtaposition to the violence and rape that appear on screen. The most famous scene with classical music depicts him having a three some with two ten year old girls in hyper speed motion while a sped up version of the fourth movement of Rossini’s William Tell Overture plays in the background. For his next film, Barry Lyndon, Kubrick again was able to play classical music because the film was a period piece, set at the time where this music would have been written and heavily listened to.

A sign of an auteur is their casts typically include a handful of select actors. Here, Kubrick deviates from other filmmakers, as he rarely reused actors, especially in leading roles. The only notable exceptions to this rule are in his early films, with Kirk Douglas starring in both Paths of Glory and as the titular role in Spartacus, and Peter Sellers starring in both Lolita and three different leading roles in Dr. Strangelove. Leon Vitali, who plays Barry Lyndon’s stepson Lord Bullingdon became Kubrick’s personal assistant for the rest of Kubrick’s career, and appeared on screen again as the cloaked man who confronts Bill at the orgy in Eyes Wide Shut.

Although Kubrick was nominated for Best Picture and Best Director several times at the Oscars, the only award that he actually ever received was for Best Visual Effects in 2001: A Space Odyssey. This is more revealing about the Oscars than it is about Kubrick, who most critics agree made better pictures than those who went off to finally win the Oscars. Kubrick is in good company as an Oscar loser, as Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock were also never appreciated by the Academy. Kubrick’s films were usually met with mixed reviews upon their original release, and it was only after years had passed did critics realize that there had never been anything like it before or since. Kubrick’s movies were not merely ahead of its time, nor were they praised for capturing the essence of it; rather, he took much larger universal concepts, and used those as a basis for his films. Eyes Wide Shut is continuing proof of the opinion shift with his films, as it is only now - a little over ten years later - that it is slowly being recognized as another masterpiece. Stanley Kubrick’s very unprolific career has had quite a prolific influence, ranging from all sorts of talented directors such as Quentin Tarentino, Terry Gilliam, Stephen Spielberg, Michael Mann, Martin Scorsese, Joel and Ethan Coen, David Fincher, David Lynch, Woody Allen, Christopher Nolan, Wes Anderson, Ridley Scott, James Cameron, and Guillermo del Toro. Kubrick is not without his detractors, among them Anthony Burgess and Stephen King, authors of A Clockwork Orange and The Shining, who both supervised second adaptations of their books in an effort to create a more faithful visual medium. Stephen King called Kubrick a man who “thinks too much and feels too little.” Stanley Kubrick’s admirers praise his originality, his endless perfectionism, his game changing camera innovations, and his ability to inspire audiences for over fifty years.

Comments

Post a Comment