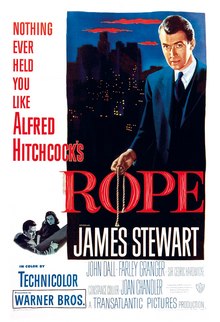

About a month ago I was watching Arsenic and Old Lace with a few friends when one of them had asked me if I had seen the Alfred Hitchcock film Rope. At the time I hadn’t seen much Hitchcock at all, but the film sounded intriguing – like Arsenic and Old Lace, it was a story about a dead man hidden in a box in the living room. A few days ago I found out that Jimmy Stewart starred in the movie and I was sold. There’s something about Jimmy Stewart that’s very approachable and familiar, kind of like an uncle or a neighbor, and I, as mentioned in a previous entry, am a huge fan of his work with Frank Capra. Hitchcock is, of course, legendary, so the combination of these two in the 1940’s film Rope makes it extremely appealing.

What surprised me most was how experimental this film was. As I lay in bed watching the film this morning I noticed that although the camera was moving, the box containing the dead man was almost always in view, and the camera was focusing on pretty much one shot for the entire film. Rope is essentially one long shot that only cuts away maybe four times total. Real long shots are extremely rare, even 127 Hours, a new film about a man in one position for that period of time, does not contain many. They are hard to film; essentially it means that absolutely no mistakes can occur, or else the entire shot has to be taken from the top. Woody Allen is infamous for them, and Andy Warhol took them to obnoxious extremes in films such as Empire and Sleep, but most directors avoid them, specifically when action is involved.

Rope starts off with a man being strangled to death in a New York apartment. The strangler, Brandon, is accompanied by his friend Phillip, who from the outset is against this idea. The motive? According to Brandon “We killed for the sake of danger and for the sake of killing.” There were no ulterior reasons here, David (the victim) had in no way harmed them, and both Brandon and Phillip were good friends of his family. They simply considered him to be an inferior human being, and superior human beings need not concern themselves with what the inferiors believe to be basic human rights. This faulty logic is almost as bad as the Brewster’s from Arsenic and Old Lace, who murdered old men to save them from loneliness. Phillip and Brandon do not have much time to express their reasoning, because soon a dinner party will start, and the game begins – they must remain nonchalant throughout to allay suspicion. The party, set in real time, is absolutely painful at times, as guests begin to wonder among themselves when David will arrive, as they eat off of the box containing his body.

This early Hitchcock gem was largely disowned by Hitchcock, who referred to it as his “experiment that didn’t work.” The reviews were unfavorable upon the film’s release, but as experimentation has caught on with modern filmmakers, this film’s influence has grown tremendously and now is viewed much more favorably then it was upon its initial release. For 1948, a period now referred to as Classical Cinema, Rope remains a dangerous experimental piece that was simply too brilliant for its own good. Don’t take my word for it – the nine takes in the film fill it out to 76 minutes, which can be streamed instantly here: http://www.novamov.com/video/4a748865ec491.

Back when you rented videos, Dad and I watched this three times in a row, fascinated by just what you're describing. You're right, this movie is mega creepy. What I particularly noticed, and admired, is the way Jimmy Steward gets more and more edgy, as he figures out what happened. I never want to watch this movie again, because of the creep factor, and because I don't have to - I'll never forget it!

ReplyDelete