I have now recently

seen Spike Lee’s new film, BlacKkKlansman,

twice, and I am left with an overflow of thoughts and emotions. Not

ignoring some poignant points made by Boots Riley (Sorry to Bother You), who convincingly argues that the real Ron

Stallworth was not the hero the movie portrays, I think it is an amazing movie.

It is the first film that really grapples with America in the age of Trump,

despite being set in the Nixon administration. It is not a film that is

designed to start a conversation exactly – maybe a riot – but it forces us to to grapple with some dark conclusions.

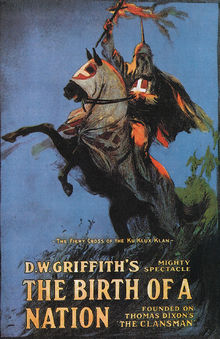

The film begins with shots from Gone With the Wind and Birth of a Nation, two films that

transformed the possibilities for what cinema could achieve, and two films that

are remembered for their reactionary views of the American Civil War. Until this week, I had never seen DW

Griffith’s Birth of a Nation; I knew

it for its place within the context of film history and American history, but I

could not imagine sitting down for a three hour black and white silent movie

from 1915. I even wrote in my college thesis (and an earlier essay on here)

that President Woodrow Wilson called it “history written with lightning”, and

although this quote seems to be apocryphal, the film was shown in the White

House, and it nevertheless expresses sympathies Wilson was well known for. I

felt that I knew the film was influential, but also extremely racist, so what

else is there?

But there is more. Birth of a Nation was the first full-length

motion picture that a mass quantity of people watched. As Harry Belafonte says

in BlacKkKlansman, it was a

blockbuster. Every single movie that you or I have ever seen in a theatre grows

out of a tradition started by Birth of a

Nation. For better or for worse, it is the alpha, the genesis; it is

cinema’s original sin. So this week, I finally sat down and watched Birth of a Nation.

I will skip past all of the

undeniable brilliance of DW Griffith’s film – the first uses of wide angles,

long shots, night photography, close ups, and an original score – and get to

the point of it – Birth of a Nation is

an evil film. While the first half of the movie has something to offer, the

whole second act is hateful propaganda. Reconstruction, the period that followed

the Civil War, is portrayed as a time when the black man ran the south for his

own gain; we see blacks getting drunk, chasing women, and abusing power. So

what can a poor white man do to stop the black beast? The defeated confederates

throw on robes, band together, and kill kill kill any blacks that would, in the

words of the film, violate the white man’s “Aryan birthright”. That line of the

movie is particularly jarring, as the film was released a full eighteen years

prior to the ascension of Adolf Hitler in Germany.

It is not just Birth of a Nation. In 1926 Buster Keaton starred and directed in The General, a Civil War movie about a train

engineer in the American South who successfully thwarts the North in battle. The

triumphant ending includes a confederate flag waving in the wind. The following

year saw the release of The Jazz Singer,

the first “talkie” – a full-length movie with sound. In it, Al Jolson plays a

musician who sings and plays in black face – this is not incidental, but rather, a core plot point. Another milestone hit, another racist legacy. Then, of

course, comes Gone With the Wind, ten

years later, a film that covers the halcyon days of the old south and the

transition to reconstruction and a post war era. Gone With The Wind's paternalist and outright racist portrayals

did not prevent it from becoming the most successful film in the history of

cinema in terms of tickets sold, a record it still holds to this day.

Why was the rise of the major

motion picture in America so steeped in white supremacy? I believe there are

two reasons. The first, and more charitable, is that for early audiences films

were, as the apocryphal saying goes,

“history written with lightning” – they created a seemingly realistic depiction

of past events. It was not just American directors who pushed the art form

forward in service of propaganda – Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and Leni Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will left their mark on cinema and continue to

echo down to us today, despite being pro Soviet and pro Nazi films. It is

hard to imagine a film having that much power today as these early marvels.

The second reason is that America was

an openly white supremacist country. In the shadow of the American Civil War, there

was a need for white reconciliation between North and South – and this came at

the expense of freedmen. This resulted in films being made, like Birth of a Nation, where North and South

(eventually) came together with common cause against the blacks. The upshot of

these historical misadventures on the part of men like DW Griffith and Thomas

Dixon was a cemented legacy of reconstruction

as a period where black people ran the South with malice - something proud, self respecting southerners had to prevent from ever happening again, which lead to an immediate resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan. Seeing clips from this film in BlacKkKlansman, coupled with the footage of Charlottesville and President Trump's response, makes me wonder how much has really changed.

Comments

Post a Comment